Quantitative results

Two hundred and two participants filled in the survey, of which 117 (58%) were complete. The response rate was 20% (Table 1). Responses per OEP ranged between 6 and 68 (Table 2– OEP Responses).

Seventy percent of the respondents provided demographic information (n = 142). Participants were mostly white (n = 95), female (n = 74), without a disability (n = 106), heterosexual (n = 89), and identifying with no religion (n = 69) (see Table 3– respondent demographics).

Most participants identified to some extent with an UrG (n = 62, 53%). Of all the students who responded (53% self-identifying as UrG to some extent, and 47% who did not identify as UrG), 67.8% (n = 80) reported that they had not been treated differently because of their cultural background or identity. Those who had been treated differently (n = 19; 16%) stated that it happened at least a few times per year (n = 15, 79%) (supplementary material 3, table a– underrepresented groups treatment). Of the 28 who reported having been treated differently, 18 reported whether they had complained: 15 had not complained (6 open-ended responses: not significant enough (n = 2), unlikely to lead to change (n = 2), fear of being identified (n = 1), happened once and felt that mistakes happen (n = 1)). Six of the 15 who did not complain did not know how or to whom to complain.

Associations between demographic characteristics and UrG self-identification found that ethnicity (merging all categories excluding White), Disability and Sexual Orientation (merging all categories excluding heterosexual) were significantly associated with identifying as belonging to an UrG group (Supplementary material 3, Table b – UrG identification vs. demographic group).

No significant associations were found between demographic characteristics and reports of being treated differently (Supplementary material 3, table c – treated differently vs. demographic group).

Of the 19 participants who reported having been treated differently because of their culture or identity, 79% (n = 15) did not report it to their OEP, 15.8% (n = 3) did, and 5.2% (n = 1) did not answer.

It was not possible to confirm or deny the adequacy of the 5-factor model proposed by Gonzales et al. [37] (Supplementary material 4), so our analysis was based on their 5-factor model (see Table 4– MCHS results). Regarding the MCHS total score, no differences were found between clinical and preclinical students (Welch’s t = -0.194, df = 79.3, p = 0.847). A weak correlation between MCHS total score and importance to individual was found (Spearman’s rho(114) = 0.27, p = 0.003), and a weak relationship between self-rating of skills and MCHS total score (rho(114) = 0.26, p = 0.005). There was no apparent relationship between MCHS total score and participants’ perception of support in the clinical environment for exploring patients’ backgrounds and experiences (rho(106) = 0.097, p = 0.3). No scores on these three questions differed significantly between clinical and preclinical students.

Qualitative results

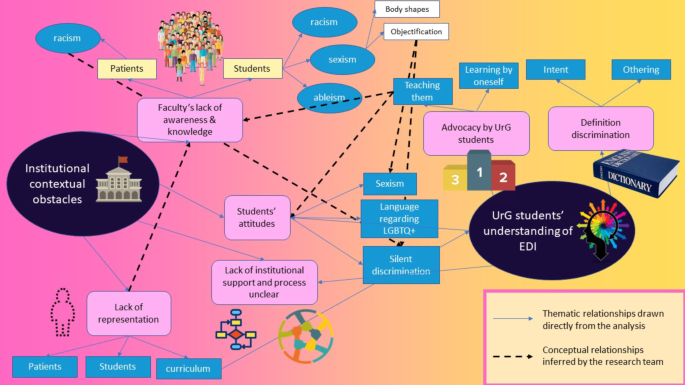

Seven groups were conducted, each were facilitated by two members of the research team (from AMM, HA, JDR, SV, YF). Data from the first six focus groups were organised into two themes which provide descriptive insights of participants’ reflections on the quantitative findings and how these results related to and resonated with their own experiences. The two primary themes were named institutional contextual obstacles (with 4 sub-themes) and UrG students’ conceptual understanding of EDI (with 3 sub-themes). The themes and sub-themes were modelled and presented to the final focus group to facilitate reflective discussions, see Fig. 2.

Model based on focus groups’ themes and sub-themes

Theme 1: Institutional contextual obstacles

The first sub-theme, Faculty’s lack of awareness & knowledge, was a commonly reported barrier.

I think there’s a lot of talk of self-reflection, at least at the OEP, and it doesn’t to me feel like all of our teachers practise that.

I’ve had more problems with staff understanding than student understanding”. (Talking about their disability)

There was no awareness, you know, of that within the class or from the tutors, in those circumstances (managing an LGBTQ + patient), what do we do, what language do we use, (…) when it was raised the tutor was sort of like, actually, I don’t have an answer, I’m not sure.

Racist, sexist and ableist comments made by staff negatively affected the way students interacted with patients in the OEPs clinics, and with other students, particularly in practical classes.

I was doing a neck and then teacher wants me to talk when I’m doing it and I say, because / when I’m doing it, I can’t talk and he made a comment, as a woman, you should talk and you should do it, you should multi-task and at that time I couldn’t say anything because I [was] already panicking and I’m doing this thing. I couldn’t say anything.

[A male tutor] put [a female tutor acting as a model] side-lying and [he] was going to crack her back but then when he pulled her shirt up her scrubs pants were like mid-way / quite / kind of showing her underwear (…) When we told him that he should pull her scrubs up, he made the thing super uncomfortable.

When they make an attack, as a joke, and people laugh, that’s positive behaviour, they’re going to make the joke again because it’s funny, so I don’t know if they can understand that it’s actually a knife that you’re throwing at someone and not just a joke.

The second sub-theme related to a lack of support from institutions for students from UrG, and a lack of clarity of processes available to them to complain about discriminatory behaviours against them.

When I was sort of going through the process of applying for the disabled students’ allowance, which I didn’t even know that I was / its existence to be honest, (…) I had to get the OEP to fill out a form and rubber stamp it and it seemed to get lost in this abyss of I don’t know where it went. (…) but there was a lot of chasing up to do [laughs] and even getting the form signed again, because I have to reapply every year, was a bit of a faff.

Participants who reported discrimination, were lacking certainty that reported these instances would lead to change.

Particularly when it’s a comment like that that’s made and it almost leaves you like gobsmacked and you’re like well what do I say to that, how do I go about telling someone about that?

The third sub-theme was Student attitudes e.g., peers making sexist comments and using negative language about UrGs.

People have said things, especially kind of bisexual tropes and things like that about you know being greedy and I know it’s / (…) people think oh that’s funny (…) it just makes you feel like you are going inward kind of thing.

I was practicing thoracic HVT with (…) some first years [students] and I started doing thoracic HVT and one of the first years asked me to do it on him, so I was like, okay, umm, I explained to him you know everything, asked for his consent and stuff, but because he was like a funny guy, he was talking all the time, I was like, okay, can you just sit down for me to do the technique and I told him my nationality before that and then he goes like oh that’s how I know you are Brazilian, your attitude, you probably go on top. I’m just like what? You know / yes, I didn’t even know what to say at this time, because I was just / I just told him, look, I’m not doing the technique, I thought, goodbye.

Participants reported instances where students from privileged backgrounds remained silent when facing discriminatory comments from educational faculty; a factor that perpetuated a non-inclusive culture, as people who used discriminatory or ‘othering’ language were not challenged to reflect on their attitudes and behaviour. In contrast, participants from UrGs felt a sense of duty to raise concerns:

I don’t create problems and stuff, but if there is something if I see it not going right, I like to raise my voice as much as I can and I try to make changes.

The fourth sub-theme was Lack of representation in the student body, patient population and the curriculum.

Everything that we get taught is 99% on like a male sex anatomy. Like I remember when I was learning how to do all the like umm cardiac testing and respiratory we were taught by a male teacher on a male body and then when it came to like a female and like you have boobs and they’re like, oh, you can’t do this bit at the front, or you have to be more careful, but then there was no example of how.

I think I felt surprised when coming into the / into osteopathy how less diverse (in student demographics? ) it is than my previous position.

I feel quite diverse but people that we see in clinic are mainly Caucasian, so I also think there’s something about the outreach of osteopathy into different cultural communities, for example, most of my family, though we’ve all been brought up here, nobody would use an osteopath (…).

When we learn about physiology and pathologies, I feel like there’s now a real effort to talk about say like black people, which is fantastic, but then you know what about Asian (…).

Theme 2: Underrepresented students’ understanding of EDI

The first sub-theme related to the definition of discrimination and echoed findings from community engagement discussions. Students distinguished between ‘othering’ and ‘intent’. Participants perceived discrimination only when actions had an intent to discriminate against individuals or communities, rather than actions that led to people or groups being treated differently regardless of intent. During the focus groups, participants reported equal treatment, but data analysis suggests instances of discrimination.

No, only in so much as, you know, the reasonable adjustments aspect, but then I’ll ask for that, but besides that, I haven’t / I haven’t had any different treatment.

I’ve definitely been treated differently as a woman and / but I’ve witnessed the / in my class Asian women being treated differently, but the Asian men not so much so.

The second sub-theme related to the advocacy of UrG students as role models for their peers. Students used their own experience of belonging to an UrG as personal knowledge to help inform their peers about what it is like to be a person from wider UrG communities. This helped to fill gaps in the EDI training or make up for a lack of training received by educators. UrG students acted as advocates to prevent wrong messages, jokes being shared, e.g.,

I think it’s / not just from my disability, but yes, from / for all other students I think when they / things come up, sometimes quite surprising things actually, it’s usually / yes, pretty interesting and helpful for all of us.

We use it [disability] sometimes in class as part of like chronic pain, as part of that kind of presentation and things like that because I have an understanding of it, whereas instead of just pulling stories out of thin air.

The third related sub-theme was that students from UrGs appeared to have a better understanding of EDI than their peers and faculty members. Students’ advocacy role included training and supporting their peers in how they should manage situations when facing patients with specific conditions, e.g. type 1 diabetes, and offered a useful insight which would be valued by patient.

I mean do they have to? Should they? I think you know, like I’ve said, the only reason I do [disclose] it is because you know I wouldn’t want to put anybody else in a tricky position if I was to, you know, have like a hypo in class or anything like that, which you know, I may do one day.

This created an environment where students from UrGs not only had to teach other students and faculty, but also had to learn on their own, as they were not able to gain knowledge from staff on topics related to UrG, and then had to teach what they learned to their peers and faculty members.

But we don’t get taught about how to deal with somebody that’s transgender or anything like that. It’s like well you’ll have to you know just find out about that yourself.

I don’t have that much of an understanding of the difference that ethnicity has on sort of different diseases and different morphologies and things like that, so it’s something (…) I’d love to learn more about.

The final mixed focus group was used to explore whether the above findings represented the experiences of these participants, and to generate suggestions for OEP action to become more inclusive. Goals thought to be quickly achievable and likely to lead to sustained change was providing urgent training for staff, and then students, to improve awareness and knowledge, and to break the issue of the cycle of unaware students becoming unaware teachers.

Lack of diversity ‘breeds’ a lack of diversity.

A lot of the main institutional barriers is the university’s lack of knowledge and the best way to deal with that is directly linked to how the under-represented students can like just you know break this barrier by teaching others and also by getting contact with the university.

Active bystander training was recommended to promote collective responsibility in challenging bias and negative views. Other suggestions included providing support for students from UrGs, countering negative views amongst peers and faculty, employing active strategies to promote patient diversity, being more equitable in services offered, and ensuring training was implemented. The final recommendation was to increase representativeness in the curriculum, as a way of training staff and students through regular exposure to up-to-date information regarding UrGs.

if the institutions were to be more aware [of EDI] and have [EDI training]…., I don’t know what training’s mandatory training’s given, but it would seem like potentially a lot of it [othering] could potentially be stopped. It just seems because you’ve got the lack of representation to faculty, race in faculty, they all sort of interlink with the other parts.

Participants felt that more and better training was needed for staff on EDI issues; a potential barrier to implementation was time, but short courses were expected to be effective.

every job I’ve ever done, either private sector, public sector, there is mandatory training and EDI’s, (…) human trafficking, (…) blackmail. (…) But I think we’re only talking like a half an hour.

Workshop results

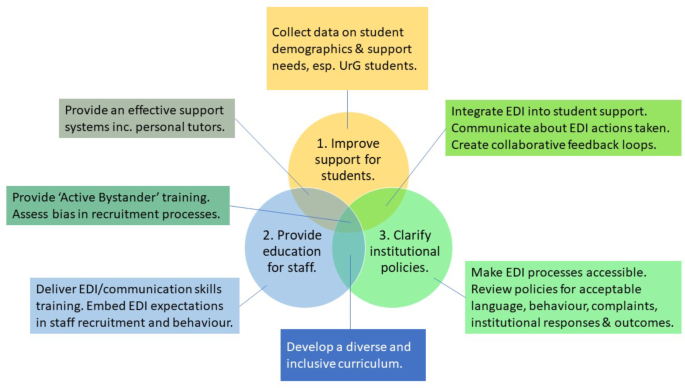

Comments from nine workshop sessions (three each on student, staff and institutional EDI issues) were combined using frequency analysis to identify key themes and recommendations for change (Table 5). The strongest theme addressed stakeholders’ opinions about staff issues (96 comments in total), with recommendations about the need to improve staff attitudes [36], increase their awareness of students’ needs [15], and enhance communication skills [26]. The second main theme was student support [49], including the need to explore barriers to change [26] and improve access to support services [14]. Two other themes focused on the need to clarify and improve institutional EDI policies and processes [26] and ways to improve representation and diversity among student osteopaths, OEP staff and patients seeking osteopathic treatment [25] (also see Supplementary Material 5).

Overlapping themes were organised in Fig. 3 in relation to the groups involved in the recommended actions.

link