Climate change is the single biggest threat to health, but does trying to prevent infections stop us from making healthcare more sustainable?

Abstract

Humans are consuming the planet’s resources faster than it can create them, while causing the planet to warm at a rate not seen before in the life of our species. This has consequences for human health, but ironically healthcare is itself a large contributor to the problem. Infection prevention is sometimes seen as a barrier to making healthcare practice more sustainable, but there are many opportunities for those with infection prevention expertise to identify and drive the changes that are needed.

Citation: Pike G (2025) Why infection prevention should lead the way in sustainable healthcare. Nursing Times [online]; 121: 8.

Author: Graham Pike is associate director of nursing and infection prevention and control, and clinical sustainability lead, Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

What do we mean by the word ‘sustainable’? The dictionary from Merriam-Webster (2025) puts it very simply: “capable of being sustained”. It also offers a more detailed definition with specific relevance to the use of resources: “of, relating to, or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged”.

In other words, for something to be sustainable, it must be possible to keep using it indefinitely, without running out of resources. Of course, all of our resources can only come from one place: the planet we live on. This is a fantastic source of what we need, constantly regenerating and renewing itself, as well as breaking down the byproducts of life, but it is not infinite. There must, therefore, be a limit to what it can provide us, and thus, to what we can sustainably use. Are we close to that limit?

In fact, as shown by the Global Footprint Network (2024), we are far beyond that limit. It estimates that in 1970 we were consuming about one Earth’s worth of ecological resources (for example, crops, livestock and fish products, soil, timber and other forest products) annually. It now calculates that annual consumption has risen to 1.7 Earths. That means that, by about the end of July each year, we use up what the Earth can produce in 12 months. That clearly cannot continue forever, because at some point there will be no more to take. We are damaging the Earth’s ability to sustain us as a species and that is obviously not sustainable.

Carbon dioxide, temperature and the impact on health

A related way in which we are causing that damage is the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) we are putting into the atmosphere. Data from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (2025) shows that the level of CO2 varied naturally between about 180 and 300 parts per million (ppm) through the past 800,000 years. The same data shows that the level of CO2 exceeded 300ppm for the first time in human history in 1911, and that it has continued to rise at an unprecedented rate since then. The concentration of CO2 exceeded 430ppm in 2025 (Global Monitoring Laboratory, 2025), so it is now >40% higher than it was for the entirety of the existence of our species before the 20th century.

Why does the level of CO2 matter? CO2, as a heat-trapping gas (NASA, 2025), causes the planet to get warmer. The more CO2, the warmer we get. And the numbers are huge. Richard Allan, professor in climate science at the University of Reading, has calculated that, at the beginning of 2023, Earth was heating at a rate equivalent to all 8 billion people alive each using 60 kettles to boil the ocean (Allan, 2025).

That amount of heat comes with consequences for human health. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the US has described how the changing climate will negatively affect communicable diseases (including vector, food and waterborne diseases), non-communicable diseases, physical injuries and mental health (CDC, 2024). NHS England (no date a) stated that:

“The climate emergency is a health emergency. Climate change threatens the foundations of good health, with direct and immediate consequences for our patients, the public and the NHS.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) said even more starkly that “climate change is the single biggest health threat facing humanity”.

Healthcare’s impact on the planet

Like any other industry, healthcare consumes resources and causes CO2 to be emitted (i.e. has a ‘carbon footprint’). In 2019, Health Care Without Harm (HCWH) published a report that calculated healthcare’s own global carbon footprint. It shows that our footprint is not small; it is more than twice that of the aviation industry, sitting at around 4.5% of global emissions (HCWH, 2019). We are creating our own patients, effectively; I could have used a different heading for this section: “Healthcare’s impact on health”.

It is important, therefore, that we find ways to reduce the damage healthcare does to the environment and to the very people we are trying to help.

How infection prevention can lead the way

As illustrated in NHS England’s Infection Prevention and Control Board Assurance Framework (NHS England, 2025), the infection prevention (IP) speciality is involved in many aspects of healthcare, including the following:

- Environmental cleanliness standards;

- Water safety;

- Ventilation safety;

- Standards for the reuse and decontamination of equipment and instruments;

- Building, maintenance and renovation plans;

- Use of linen;

- Waste management;

- Use of personal protective equipment.

Changing how any of the above are managed to reduce environmental impact will require the support of IP teams. This puts those teams in positions where they can either enable such change or be a barrier to it. Given the critical nature of the climate emergency and the heavy use of resources in many aspects of IP, it is important that IP practitioners are aware of how their decisions will affect carbon emissions as well as patient safety. It does not have to be a conflict between IP and sustainability; indeed, there are many areas in which IP practitioners can lead the way. Below are examples of where there is a clear synergy between the two.

“Those with expertise in infection prevention have a duty to the planet to ensure their speciality is not misused”

Gloves

As an IP practitioner myself, I am very conscious of how much healthcare delivery has become more resource-intensive over time because of infection risks. Consider, for example, the fact that gloves were not widely used before the 1980s – even for contact with body fluids – and that their increased use arose initially as part of what were then termed ‘universal precautions’, a response to the emerging HIV epidemic (Wilson, 2006).

Glove use indications were added to in the late 1990s when the concept of ‘contact precautions’ was introduced for patients known or suspected to be infected or colonised with specific microorganisms (Wilson and Prieto, 2021). An estimated 1.4 billion gloves are now used across the NHS every year (Royal College of Nursing, 2024). That means around 160,000 gloves are being used every hour.

Unfortunately, evidence suggests more than half of that glove use (700 million gloves) may be inappropriate and may contribute to a risk of cross-contamination in 49% of episodes of care (Wilson et al, 2017). This inappropriate use may be due to an inconsistency between the concepts of ‘standard’ and ‘contact’ precautions, leading to a perception among staff that gloves should be routinely worn for contact with all patients to protect themselves (Wilson and Prieto, 2021). Gloves are only needed for exposure to blood or body fluids (NHS England, 2024) or for handling hazardous chemicals (Health and Safety Executive, no date). Sadly, as Ratcliffe and Smith (2014) pointed out, the overuse of gloves may have reduced the therapeutic use of touch, adversely affecting the nurse–patient relationship.

So we can see how both the actual risk of infection and the perception of such a risk have driven the overuse of gloves across healthcare. As with all consumption, there is a carbon footprint associated with this.

Rizan et al (2021) calculated that an individual glove, across its lifetime from manufacture to disposal, causes 26g of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) to be emitted. We can calculate, therefore, that the 700 million gloves used unnecessarily each year have a carbon footprint of 18,200 tonnes of CO2e.

With the WHO rating climate change as the single-biggest threat to human health (WHO, 2023), all health professionals, but especially IP practitioners, have a duty to rectify this overuse of gloves. It saves money, reduces carbon emissions, and improves patient safety by reducing the cross-contamination risk (Wilson et al, 2017) and increasing therapeutic touch (Ratcliffe and Smith, 2014). Great Ormond Street Hospital’s pioneering Gloves Off campaign, launched in April 2018 (Mitchell, 2019), and other similar initiatives, have done a lot to raise awareness of the issue.

“As an easy place to start, I recommend looking in your bins”

Single-use devices

As Lee et al (2024) described, there has been a move toward single-use devices across a range of healthcare equipment, with the guarantee of sterility being one of the motivations for that trend. As the authors pointed out, in some cases (such as with single-use blood pressure cuffs), these items are seen as being important to the prevention of infection despite there being existing guidance for safe decontamination of the reusable form of the product.

Other examples where that is the case include textiles in theatres, where, for example, single-use table drapes are widely used despite a review by the WHO called Global Guidelines for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection finding no evidence of difference in surgical site infection rates when single-use versus reusable drapes were used (Brighton and Sussex Medical School et al, 2023).

Of course, as Lee et al (2024) highlighted, lack of space, staff or time for reprocessing of reusable versions of some devices can be significant barriers to change. It is important that we do not add to those very real logistical challenges by emphasising a risk of infection where none exists. Again, I would argue, those with expertise in IP have a duty to the planet to ensure their speciality is not misused in this way.

Intravenous cannulas

The above examples highlight where a better understanding of IP principles and evidence can be useful in facilitating healthcare that is less impactful on the planet. There are other examples of a potential change to practice where the benefits to both IP and sustainability are even more closely aligned.

Take the use of intravenous cannulas, which are well-known and well-documented as presenting a risk of infection, such as by Zhang et al (2016). An improvement project at Charing Cross Hospital (NHS England, no date b) found that 86% of patients attending the emergency department were cannulated, but that over 40% of those cannulas were never used and that 68% of patients reported pain and discomfort associated with cannulation.

There is an obvious improvement opportunity here: that of making cannulation more targeted to those who really need it, which would reduce infection risk, carbon emissions and cost.

Taking action

At my organisation, Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (GWH) in Swindon, we were approached by NHS England in autumn 2023 with a request to put together some real-life examples of sustainable quality improvement work where IP expertise and input were a key part of the process. This was part of a scheme to support the development of exemplar organisations for various aspects of sustainable healthcare, meaning we were selected to pilot this from an IP standpoint.

Our report into this work (Fig 1) was released in December (GWH, 2024) and some examples from it are discussed in more detail below.

GWH example 1: frequency of changing sheets

We felt that a good example of a routine practice performed with IP in mind, but for which guidance and evidence were lacking, was the daily changing of all patients’ sheets. We were able to confirm through networking that this is not standard practice in all countries, so a move to less frequent changing would not be unprecedented. We were, however, keen to ensure that both staff and patients were supportive of the move.

Our first contact was with the linen service manager, who expressed support and suggested it may bring an additional benefit in the reduction of lost property being inadvertently bundled up with sheets.

The following proposal, as a draft for public consultation, was then approved by the trust’s infection control group and finally by the senior nursing, midwifery and allied health professionals group:

- All linen must be changed between patients;

- Sheets and pillowcases: change twice weekly (Sunday and Wednesday);

- Blankets: change when soiled or contaminated;

- Patients requiring isolation: change all linen daily;

- Any wet, soiled or contaminated linen: change immediately.

Augmented care areas were excluded from the proposed change (at GWH this is our critical care, neonatal and haematology/oncology wards).

The trust’s patient engagement lead shared this proposal with a variety of community groups and with members of the trust from the local community. We were pleased to find that the only comments received were positive and supportive. Here are two examples of the feedback received:

“With regard to changing sheets every day, I agree that twice weekly for the majority of the patients is a good idea, unless, as you have stated, they need to be changed for whatever reason for certain patients. It will save so much time, money, water, energy and will be less hassle for the patients too.”

“I think this is a very sensible idea. [Daily changing] is not necessary for certain groups of patients. It is a waste of time and money. I would not have a problem with this if I were an inpatient.”

At the time of publishing the report, we had not yet trialled this change in a clinical area. We have subsequently conducted a three-month trial on our gastroenterology ward led by two healthcare support workers. Patients still have their beds made daily and the ward staff have deliberately changed their language on this, from “can we change your sheets?” to “can we straighten up your sheets?”.

Staff- and public-facing posters were displayed to explain the change. The outcomes have been positive:

- No concerns or complaints from patients or visitors;

- Staff report it has released time for patient care;

- 2,503 fewer items of linen used in February 2025 compared with the baseline of November 2024;

- Associated financial saving of just over £700 per month.

We have now added two more wards to the trial and will continue to monitor

progress.

GWH example 2: reducing the use of couch roll

Couch roll (often known as blue roll) was routinely used across GWH to cover examination couches and, like the previous example, this practice was performed with an IP aim. Couch roll, however, is not impervious, does not cover the whole couch and is easily ripped. It, therefore, does not remove any requirement to clean couches between patients. For most patients, we were unable to identify a benefit to its use.

GWH spent £11,000 annually on couch roll which, using figures from a similar improvement project at Nuffield Health Warwickshire Hospital (Ford, 2023), we were able to approximate as being 155 miles of couch roll causing five tonnes of waste.

Guidance was shared with all departments using couch roll, pointing out that it was not required for IP purposes and suggesting its use could be reviewed.

One of the highest users of couch roll was the emergency department, with 243 rolls used in a three-month period before the change. In the latest similar period, none was used. Several other departments have also been able to stop using couch roll completely, including occupational health, podiatry and our main outpatient department.

While couch roll still has a use in some cases (for example, when examining non-potty-trained infants), our intent is now to work with the remaining users and identify where use can be reduced further.

GWH example 3: glove use reduction in critical care

NHS England had requested that we include a glove reduction project as part of our overall scheme. Knowing that the Intensive Care Society (ICS) had recently collaborated with the Infection Prevention Society on developing a suite of resources for implementing a glove reduction project in a critical care setting (ICS, no date), we spoke to our critical care team. Two staff nurses were keen to lead on the project and they were supported by the trust’s quality improvement team.

Helpful aspects of the ICS package are the inclusion of an audit tool, an implementation guide and posters. The audit tool helps establish a baseline level of inappropriate glove use, which includes information on the risk of cross-contamination and on whether hand hygiene guidance was followed.

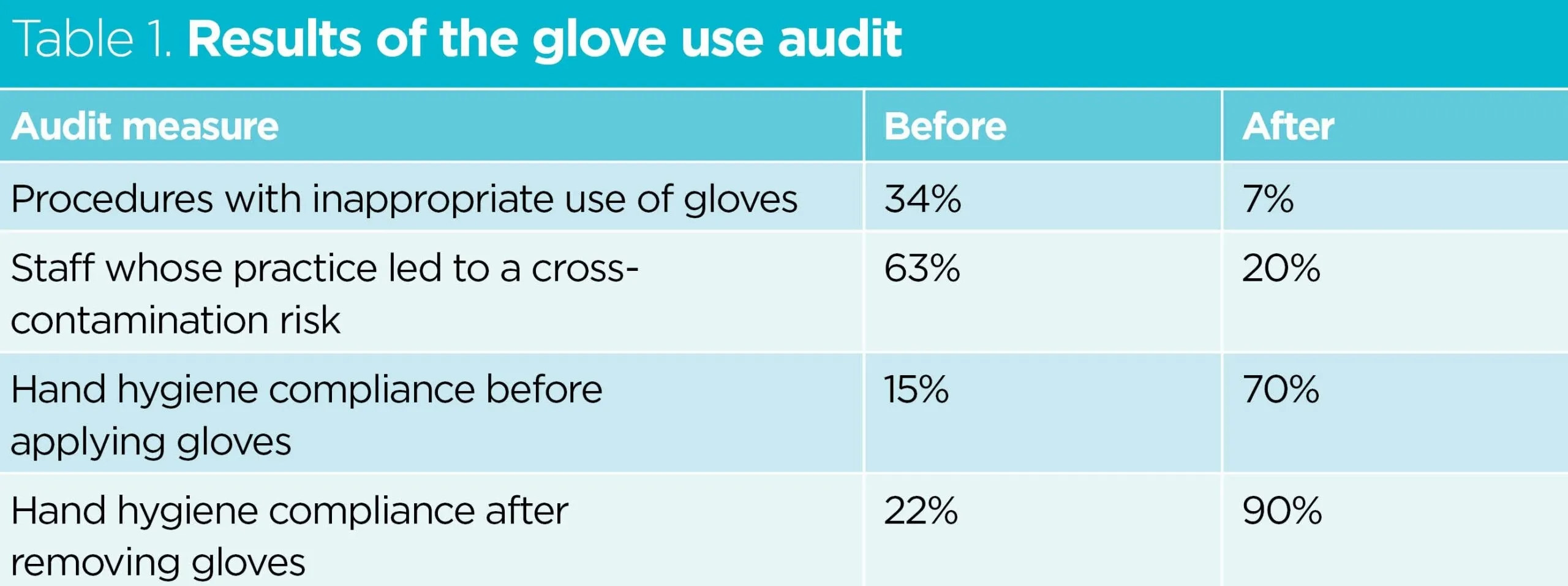

A baseline audit was performed before a range of improvement measures was put in place, including posters, teaching, emails, newsletters and a webinar link, with a post-intervention audit after two months. Results are shown in Table 1.

Data from our procurement team showed a 22% reduction in glove use which, if sustained, would lead to 1.6 tonnes of CO2e emissions being prevented annually while saving £1,382.

Wider application of the project

Although designed with a critical care setting in mind, there is much in the ICS package that is applicable in any healthcare setting. The leads for the project have since been supporting other teams, such as those in the emergency department and endoscopy, to launch similar projects. Overall, our trust has seen more than one million fewer gloves used in the 2024-5 financial year than in 2023-4, preventing 27.4 tonnes of CO2e emissions. This is only a 10% reduction, so we anticipate further savings are possible.

GWH example 4: reusable tourniquets

There are now reusable tourniquets available, which can easily be decontaminated between patients, using standard wipes. We undertook a trial of the reusable tourniquets, having first calculated that each would need to be used 935 times for the change to be cost-effective. Trials are still underway, but early indications are that they last for at least this long (the manufacturer advises 10,000 uses are expected) and feedback from patients is positive (87% favourable). Some departments (for example occupational health) have already made the decision to switch permanently to the reusable devices.

GWH example 5: cannulation reduction

Our emergency department team reviewed their cannulation protocols, working as a multidisciplinary team to define which patient presentations required a cannula and which did not. Over the three months of the project, procurement data showed this led to a 29% reduction in cannulas ordered. There were no adverse events noted but, reflecting on the findings at Charing Cross Hospital (NHS, no date b), there are likely to have been improvements to the patient experience and to the risk of infection.

Conclusion and next steps

The climate is changing, driven by human activity of which healthcare is a significant part, and this has implications for human health. If we are to reduce healthcare’s impact on the planet and contribute to reducing the health effects of climate change, healthcare needs to become a less intensive user of resources. IP has driven healthcare to higher levels of consumption, for example, of gloves and other single-use disposable items. Reversing that trend requires the application of IP principles to understand where use can be reduced or even eliminated, and when reusable alternatives can be implemented.

This is a topic that healthcare bodies are increasingly devoting their attention to. Many healthcare royal colleges, professional and specialist societies are working to reduce the impact of their spheres of practice. Whatever speciality you work in, you are likely to find advice on how to make your practice more sustainable on the website of a relevant institution. The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare is also a good source of information, as well as providing networks where you can share ideas with like-minded professionals.

As an easy place to start, I recommend looking in your bins. What is in there that could be used less often or swapped for a reusable alternative? Talk to your colleagues and manager and see if you can make that change. Then share it with others, so we can all make progress on this together.

Key points

- Consumption of the Earth’s resources is currently at a rate 70% higher than the planet can produce

- Climate change will affect every aspect of human health and is a major threat to our species

- Healthcare’s consumption of resources is often driven by attempts to mitigate infection risks

- Infection prevention expertise aids understanding of where consumption can be reduced

Allan R (2025) Reconciling Earth’s growing energy imbalance with ocean warming. blogs.reading.ac.uk, 24 March (accessed 5 June 2025).

Brighton and Sussex Medical School et al (2023) Green Surgery: Reducing the Environmental Impact of Surgical Care. UK Health Alliance on Climate Change.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024) Effects of climate change on health. cdc.gov, 29 February (accessed 5 June 2025).

Ford S (2023) Call to reduce waste by getting rid of paper couch covers. nursingtimes.net, 15 May (accessed 5 June 2025).

Global Footprint Network (2024) Earth Overshoot Day 2024 approaching. footprintnetwork.org,

24 July (accessed 5 June 2025).

Global Monitoring Laboratory (2025) Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide (CO2). gml.noaa.gov (accessed 5 June 2025).

Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (2024) Infection Prevention & Control and Sustainability. Exemplar Site Project Report. GWH.

Health and Safety Executive (no date) Choosing the right gloves to protect skin: a guide for employers. hse.gov.uk (accessed 16 June 2025).

Health Care Without Harm (2019) Health Care’s Climate Footprint. HCH.

Intensive Care Society (no date) Gloves Off in Critical Care. ics.ac.uk (accessed 5 June 2025).

Lee PS et al (2024) Greening infection prevention and control: multifaceted approaches to a sustainable future. Open Forum Infectious Diseases; 12: 2, ofae371.

Merriam-Webster (2025) Sustainable (adjective). merriam-webster.com, 25 May (accessed 5 June 2025).

Mitchell G (2019) Glove crackdown saves trust £90k and reduces waste. nursingtimes.net,

7 August (accessed 11 June 2025).

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2025) Carbon dioxide. climate.nasa.gov, April (accessed 5 June 2025).

NHS England (no date a) Health and climate change. england.nhs.uk (accessed 5 June 2025).

NHS England (no date b) Reducing unnecessary cannulation at Charing Cross Hospital.

england.nhs.uk (accessed 5 June 2025).

NHS England (2025) National Infection Prevention And Control Board Assurance Framework. england.nhs.uk, April (accessed 16 June 2025).

NHS England (2024) National infection prevention and control manual (NIPCM) for England.

england.nhs.uk, 23 May (accessed 16 June 2025).

Ratcliffe S, Smith J (2014) Factors influencing glove use in student nurses. Nursing Times; 110: 49, 18-21.

Rizan C et al (2021) Environmental impact of personal protective equipment distributed for use by health and social care services in England in the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine; 114: 5, 250-263.

Royal College of Nursing (2024) Hand hygiene: top tips for skin health and glove use. rcn.org.uk, 1 May (accessed 15 July 2025).

Wilson J (2006) Infection Control in Clinical Practice. Elsevier.

Wilson J et al (2017) Applying human factors and ergonomics to the misuse of nonsterile clinical gloves in acute care. American Journal of Infection Control; 45: 7, 779-786.

Wilson J, Prieto J (2021) Re-visiting contact precautions – 25 years on. Journal of Infection Prevention; 22: 6, 242-244.

World Health Organization (2023) Climate change and noncommunicable diseases: connections. who.int, 2 November (accessed 5 June 2025).

Zhang L (2016) Infection risks associated with peripheral vascular catheters. Journal of Infection Prevention; 17: 5, 207-213.

Help Nursing Times improve

Help us better understand how you use our clinical articles, what you think about them and how you would improve them. Please complete our short survey.

link