Quantitative survey

A total of 333 students from different colleges participated in the study (Table 1). The majority of the participants were Medical students [128 (38.4%)], followed by Nursing [105 (31.5%)], Dental [68 (20.4%)], and Pharmacy students [32 (9.6%)].

Maximum participation was from the 2nd year, and the least from the 5th year. A very high number of females participated [227 (68.2%)] in the survey compared to males [106 (31.8%)]. More than half [178 (53.5%)] had good academic scores with a GPA of more than 3. Questions were asked regarding the Qualities, Approaches, and Behaviors of their teachers that they think motivate them to learn. There were significant differences of opinion among students of different colleges (Table 2).

The proportion of students perceiving a characteristic of a teacher as very important factor for motivation to learn was compared across colleges. Most of the nursing students [50 (47.6%)] believed that impression (well dressed, good personality) does matter a lot for the motivation to learn; however, dental college students [4 (5.9%)] considered it least important (p < 0.05). There was a significant association observed between Inspiring, Friendly, Compassionate, Trustworthy, Well-intentioned, Reliable, and Instilling confidence factors among students of different courses (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

There was a set of questions asked to students on their views on teachers’ characteristics that enable a strong student-teacher relationship. Students had mixed opinions about the qualities, attitudes, and behavior. Most students regarded being friendly, having a positive attitude towards students, and being reliable are the most important contributors to strong STR. Reliability was the most important factor, with 75.8% of medical and 68.8% of pharmacy students sharing the opinion that the reliability of the teachers is a very important aspect. This was statistically different from the other two colleges (nursing and dental) (p < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the students of different colleges about other attributes of the teachers (Supplementary Table 1). When the factors for motivation to learn and strong STR were compared among students of different colleges, there was no statistically significant difference in any of the attributes [kappa value 0.186–0.383] (Supplementary Table 2).

In Sect. 3 of the questionnaire, students of different colleges were asked about their views on teachers. The proportion of students agreeing to all of their teachers’ actions in a certain scenario was compared across colleges. The results show that the highest proportion of pharmacy students believed that teachers answered the students’ questions during the lecture, and teachers treat all students with respect, while medical students expressed positive views on teachers also helping them outside the class (Table 3). A marginal number of students from Nursing 22 (21%) believed “only some of them receive respect” (p < 0.05). The views differed significantly among the students of different colleges with regards to teachers helping them outside the class, and treating students with respect (p < 0.05). There were differences of opinion regarding teachers accepting students’ criticism of their opinions willingly, although it was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

The views of the students on attendance, discipline in the class, and its effect on STR, reflected mixed views. The proportion of students strongly agreeing to statements on attendance, discipline in the class, & its effect on STR was compared across colleges. Most of the students favored disciplinary actions for students causing disruption during the class, with only few disagreeing or strongly disagreeing (Table 4). There was statistically significant differences in views of the students regarding whether it is proper action to expel the students or ignore the action, for the students causing class disruption (p < 0.05). The majority of the nursing students strongly believe that, if there is a disruption in the class, the most proper action by the teacher is to expel the student (p < 0.05). The majority of students either agreed or strongly agreed that STR can positively or negatively affect academic achievements (95.5%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

A teacher’s teaching methods, students’ opinions and trust also affect STR. A major proportion of students across colleges in general think that teachers who use references for the lecture are good teachers, and they trust the advice of their teachers (> 90%) (Table 5). Students are more interested in attending lectures for teachers who use interactive teaching rather than spoon-feeding (68.2%). The students also report either very good or good relationships with their teachers, with only 2.1% (n = 7) reporting bad or very bad relationships. However, the nursing and pharmacy students have significantly better (very good Good) relationships with their teachers (p = 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 6 shows the relative perceived importance of teachers’ characteristics influencing students’ motivation to learn. Students perceiving a particular characteristic as very important were compared. When compared year-wise, there were statistically significant differences between different years of students in the factors they consider that motivate them to learn. We found that the major proportion of students from the second year rated high for exciting, inspiring, friendly, and compassionate as very important, with the highest proportions of 57.8%, 60.0%, 63.3%, and 57.8% respectively. The importance of this factor declined in the later years, especially in the 5th year at 31.8%, 31.8%, 40.9% and 38.6%. The students of 1 st and 2nd years showed higher values for positivity (62.1% and 63.3%), caring (57.6% and 56.7%), and trustworthiness (60.6% and 61.1%), and it showed a notable decline in 5th year students-40.9% in all aspects.

“Positivity towards students” was highly valued, especially in the 1 st and 2nd years (62.1% and 63.3%, respectively). However, this importance was reduced by the 5th year (40.9%). “Caring” was most valued in the 1 st and 2nd years (57.6% and 56.7%, respectively). Its perceived importance decreased by the 5th year (40.9%). The trustworthiness of instructors was particularly important in the 1 st and 2nd years (60.6% and 61.1%, respectively), with a notable decline in the 5th year (40.9% in all three domains).

As shown in Table 7, the proportion of students strongly agreeing to statements on attendance, discipline in the class, & its effect on STR was compared across years of study. A good proportion of students, especially in the 5th year (36.4%), strongly agree that ignoring the disruption is the most proper action and has shown a statistically significant difference over the years. A significant portion of students believe that their attendance is affected by the student-teacher relationship, with the highest agreement in the 3rd year (43.1%) and 5th year (43.2%) (Table 7).

A considerable number of students strongly believe that teacher performance is influenced by students’ attendance, with the highest in the 2nd year (38.9%) and 5th year (40.9%). Most students across all years agree that reprimanding a student is the appropriate action, with the highest agreement in the 2nd year (32.2%). The majority of students across all years strongly agree that the student-teacher relationship can affect academic achievement, with the highest agreement in the 1 st year (65.2%) and 5th year (65.9%). However, there was no statistically significant difference among the students of different years.

Table 8 shows the results of the views of students about teachers teaching methods, factors affecting trust in the teacher, and their own STRs. The proportion of students agreeing to certain statements were compared between years of study. We found a statistically significant proportion of students are influenced by previous students’ opinions, which was notably high, particularly in the 2nd and 4th years (72.2% and 72.1%, respectively) and a strong preference for interactive teaching over spoon feeding was evident, particularly in the 1 st year (77.3%) and the 3rd year (75.4%). Other sections showed different views among the different year students but were not significant.

Furthermore, these comparisons were also done between different genders and the grade point average (GPA) of the students. In each of the sections, proportion of male students having a positive perception was compared to the proportion of female students.

The female students considered trust as the most important aspect of motivation to learn. They also considered trusting the teacher’s advice and following the teacher’s decision to have a positive influence on a strong STR. There was no statistically significant difference between the views of male and female students on attendance, and discipline as important contributors to a good STR (Table 9). Both male and female students had similar opinions on other motivating factors for learning, as well as factors influencing a good STR [Supplementary Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. When responses were compared between students with a GPA of more than 3 (high achievers in the context of this research) and less than 3 (low achievers), 97.9% of the students viewed their relationship with their teachers as good and very good. Students also agreed that their attendance in class, and teachers’ performance in class is influenced by the individual STRs (73.2%, and 73.5% respectively) [Supplementary Tables 8–12]. The students had significantly different opinions about whether it is a proper action to ignore it when there is a class disruption [55.5% of high achievers agreed vs. 63.2% low achievers (p = 0.006), and whether the teacher who uses references for the lecture (book, handout, etc.) is a good teacher [98.9% of high achievers agreed vs. 94.2% low achievers (p = 0.017)]. [Supplementary Tables 8–12].

Qualitative study (interviews)

A total of ten faculty and TAs participated, with six females and four males, reflecting the gender ratio in the university. The students were interviewed till a saturation of answers was obtained. Saturation was determined by the point at which no new codes or insights emerged from successive interviews. After nine student interviews, the team observed that the responses repeated prior themes without introducing new concepts, suggesting thematic saturation [33, 34]. Finally, nine students were included, with five females and four males [34].

The questions used were

-

1.

What do you consider a successful student-teacher relationship?

-

2.

What are the qualities that a teacher should have in order to develop a positive relationship with students?

-

3.

How does your relationship with your teachers/students influence your emotional and mental well-being?

-

4.

What is the role of technology, you know, in building this relationship between a teacher and a student?

-

5.

Would you like to make some recommendations to policymakers for creating policies that support student-teacher relationships?

Thematic analysis

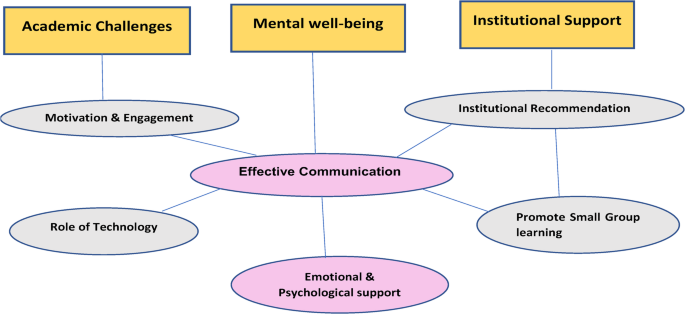

Thematic analysis was used for the data obtained from the interviews using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework for thematic analysis. The thematic analysis process with the actual responses highlighted key phrases or concepts for questions, such as easy reach, easy to communicate, full transparency (used more than once), non-judgmental, familiarization, considerate, encouraging the student to learn, and for the future, if planning in the field. Ultimately, five themes were refined to accurately represent the data: emotional and psychological support, effective communication, and transparency; role of technology, and institutional recommendations (Table 10).

While 80% of participants said that they have successful student-teacher relationships with one or more individuals, 20% felt it was unnecessary or time-consuming. The thematic analysis process with the actual responses highlighted key phrases or concepts for Q2 were openness, humor, kindness, good listener and advisor, empathy, open to conversation, positive attitude, tolerance, being friendly, balance between being friendly and strict, being patient, and good administrative and interested in teaching. The themes that emerged were being a good teacher, communicator, and possessing interpersonal qualities are most important for a good student-teacher relationship. The thematic map of the analysis is provided in Fig. 1.

All the participants believed that relationships with your teacher/student influence the emotional and mental well-being of an individual. This was more affirmative in students (having good STR) compared to the teachers, who felt that it was important but did not necessarily have a greater impact. The actual responses for Q3 were if the relationship (for the student with the teacher) is bad, the student loses interest in the subject, and does not perform well; with a bad STR student is closed off. It was interesting to note that students felt bad STR affects their learning of the subject negatively, despite putting in the same effort, compared to subjects in which they have good STR. This was related to the mental well-being and feelings around the subject.

Nine out of the ten participants felt that technology has an impact on the STR. The thematic analysis process, with the actual responses highlighted key phrases or concepts for Q4, was connectivity, timely communication, and easy approachability. While the students were positive about the use of technology, teachers felt that technology should be appropriately used for optimal benefits. Two participants strongly felt that technology is good for communication, but it can hamper STR adversely. The concern was the perceived lack of actual human interaction with digital use.

The majority of participants did not have any recommendations for Q5. Some of the actual responses “We need to reduce the class size so that there can be more focus on building STR”, the STR is always better with small groups, so we need more small-group teaching”, and “We have the surveys which give us an opportunity for specific suggestions to teachers”. These highlight a wish for better STR, which they perceive can improve teaching and learning.

In summary, the students emphasized ease of communication, transparency, empathy, and feeling encouraged, linking positive STR to better mental well-being and academic engagement. They preferred approachable, kind, and balanced teachers, and viewed technology as helpful for timely interaction. Teachers, while recognizing STR’s importance, were more reserved about its emotional impact, highlighting professional boundaries. They valued being good advisors and noted that technology, if misused, could hinder authentic interactions. Both groups suggested small-group teaching and better feedback mechanisms to improve STR. Overall, students focused on emotional connection, while teachers leaned towards structure and responsible interaction.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative results

Quantitative surveys revealed patterns of preference and significant associations between teacher characteristics and student motivation, while qualitative data explored the rationale behind it. The quantitative survey findings show qualities like impressive, inspiring, compassionate, and reliable were highly valued by students across different colleges [Table 2]. This was reinforced by qualitative interviews, where students further emphasized the importance of emotional and psychological support, trust, and interpersonal warmth as fundamental components of effective STR. The strong preference for reliability and trustworthiness among medical and pharmacy students (e.g., 75.8% and 68.8%, respectively) mirrors qualitative comments highlighting that trust and emotional safety with teachers significantly impact students’ willingness to engage and seek help [Table 10]. Students’ appreciation of respectful behavior and helpfulness outside class is consistent with qualitative themes around approachability (contacting teachers via WhatsApp and receiving timely responses) [Tables 3 and 10]. The survey showed that students agreed that STRs affect attendance and discipline (e.g., 38.4% strongly agreed that attendance is affected). Students also stated that poor relationships led to disengagement, while supportive STR leads to better attendance and class participation [Tables 4 and 10]. The qualitative responses showed that students valued non-judgmental teachers who gave clear guidance and created an open environment. This role as advisors was supported by quantitative data, where over 90% of students reported trusting their teachers’ advice [Tables 5 and 10]. While quantitative data showed a preference for interactive teaching methods, interviews revealed that such methods (e.g., small group teaching) improve emotional engagement and enhance students’ motivation to learn.

link